Have you ever wondered what it would feel like to win the lottery? Maybe there’s disbelief at first, followed by shock and then overwhelming joy. What if winning the lottery could be the best and worst thing? What if it meant leaving your homeland behind to build a new home in Omaha, Nebraska? What if you and your sibling are the only brown faces at school and you’re treated differently because of it? Would you still want to win the lottery? Multimedia artist Eunice Adounkpe knows what it’s like to win the lottery – and no, not the monetary one. Yet, despite the circumstances stacked against her she made the choice to rise above racial, cultural and social odds. Yeah, she’s pretty darn tough.

Around 16 years ago, a family living in the Western African country of Niger immigrated to the United States as winners of the Diversity Immigrant Visa Program (DV Program). They settled down in Omaha, Nebraska with their two daughters in the hopes their children would receive the best education. Eunice Adounkpe received a different kind of education beyond the classroom. She learned about racial and language barriers and how to be thick-skinned as she encountered racism, prejudice and bias during elementary school all the way into college in Hastings, NE. “…We were kind of outsiders in a lot of ways. Going to college away from home definitely helped.” Hastings is about two and a half hours away from Omaha, which Eunice says put her “even more so in the middle of nowhere. You could get from one side of the town to the other driving probably 5 minutes flat.” She received an academic scholarship at Hastings College, a school primarily made up of athletes. Not fitting into the stereotypical athlete profile, she instead dove into the world of arts and speech and debate. It was in this world she was able to find allies and mentors. “I got quite a few mentors in the arts in general, which helped me find my voice on many different levels.”

“Speech and debate allowed me to learn how to speak up for myself. Because in my culture, women don’t speak in general. We’re expected to be seen not heard.”

“Finding an activity in which I could relay my stories and experiences through poetry, through writing, through performance allowed me to develop my identity a lot better and to be clearer with what I wanted from the world I was living in.” Drawing, sculpting, and creating allowed her to give physical form to her thoughts and words. “Which is a lot harder for someone who isn’t a native English speaker.”

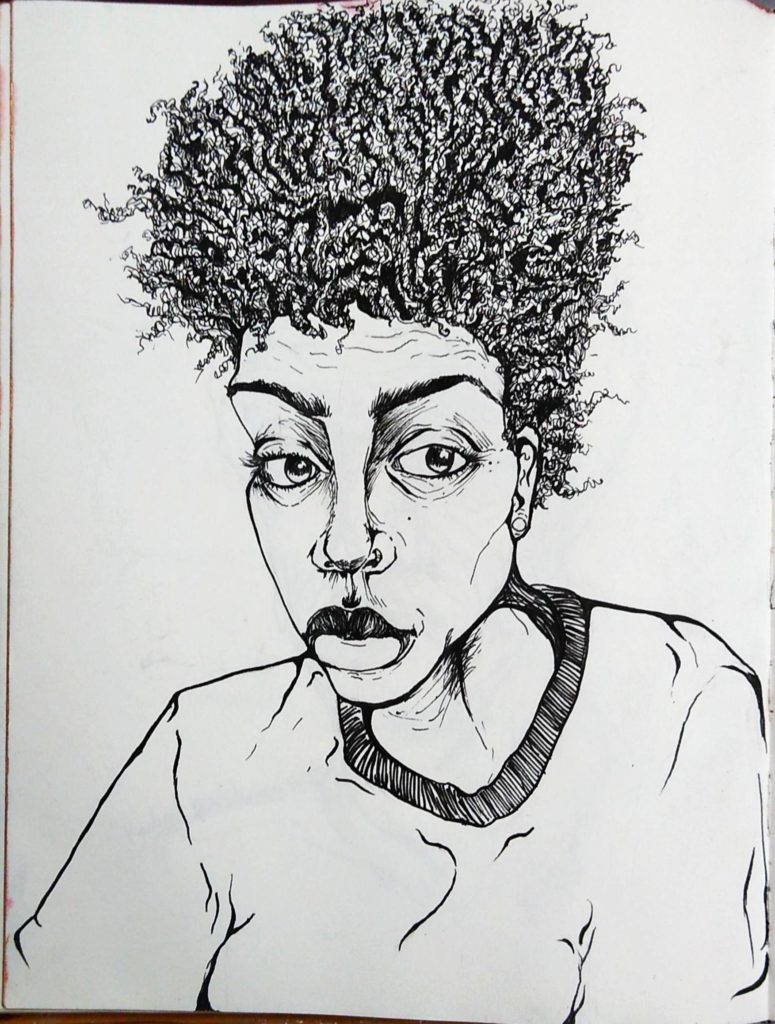

Self portrait entitled “Distorted Potential” by Eunice Adounkpe

If you have ever taken an art history class or received formal training, there’s a common thread wrapped around what is acceptable. It tightly binds together the rules and practices embedded into the fabric of what is considered fine art. This thread comes in one color – white. “Art in general has been white-washed. There are standards of what is considered beauty. There are standards of what is considered proper art that I do think the Black community has done an amazing job of working to push the boundaries of. So being in this age where Black artists and Black owned companies are prospering is a blessing because I get to see the works that I make find a spot within a community in a world that is predominantly white.”

“You make the space you want to be in. You make the environment, the community you want to see for yourself.”

There aren’t a lot of African female artists but there are Black artists she admires. “Knowing that it’s possible for them allows me to know it will be possible for me. But I do believe the possibility is what drives me to constantly try and post, constantly connect with other artists around me.”

Getting to this point however took time. Eunice recently moved to New York, experiencing yet another jolting cultural shift. Over the last three years or so, she has been creating what beauty means to her but first, she discovered a need to lift the veil created by her environment. “On the cusp of me moving here, I was changing my art in a lot of ways…I started to notice things about the way I was drawing certain people or my perception of what beauty was for the longest period of time.”

“I found myself shifting the way that I was drawing and going for characters that looked and embodied me, embodied what I wanted beauty to stand for, for me. What I wanted the beautiful people around me to see for themselves.” It was no longer about creating the “proper” way, or pleasing a predominantly white audience. It was about pleasing the artist and creator inside of herself. When she made art that did not represent her, she found it hard to communicate to it and with it. There was less passion and less depth in the creation process. “But when I had to push myself to create Black art or Black characters or Black people, I found myself working twice as hard to do it as accurately as possible. I didn’t want to show beauty in a less than accurate way. And when I started realizing that, the more I realized that this is why I needed to create art like this.” And so she poured herself into researching African artists from her childhood and the art making processes of Niger, her home. What she found was that there were no rules. “It was just doing because it brought that thing out in its raw and beautiful state.”

“I see myself every day. If I’m not able to create something that looks like me, then what does that say about me as an artist?.”

I was reminded of something she had brought up earlier in our conversation about the scarcity of African female artists. In this journey of defining what is beautiful and what is art, she stopped asking about whether or not what she created would be bought and started looking at whether she would be happy to have made it. For her, artists are creators capable of bringing things to life. The authenticity can easily be seen in her sculptures, her drawing style, and her voice. By listening to the call to create Eunice was becoming one of those much needed African female artists.

“Pharaoh Pharaoh (Let my people go)” painting by Eunice Adounkpe

In Brooklyn, she spends her time exploring as much as possible, looking at other Black artists and the world of art outside of the US. She enjoys people-watching (with caution), writing a lot and going to poetry events to expand and renew herself. She finds inspiration in the conversations with her students as their Speech and Debate coach. Other times, inspiration is found in the stories of her family – her grandmother, her parents. We spoke about how art can seem inaccessible, like a luxury afforded only to the wealthy and elite. Yet, art is not about being able to afford the best products. There is art in the use of resources all around us. Examples can be found in the DIY community, in the recycled materials used by Ghanaian artist El Anatsui to create masterpieces, in the dyed fabrics made by the hands of women in Niger.

“Worth isn’t established based on newness…The value comes from the creation of it.”

Eunice Adounkpe working with sculptures as an undergrad

In the last couple of months, Eunice has been painting. Her last show in Omaha showcased a primarily portraiture series titled “We Are Golden” where she was able to present herself as a Black artist creating Black art to her predominantly white audience. She is now working with friends and colleagues to paint natural Black figures. She says she’s going for “raw Black beauty” and has her eyes on creating around 25 paintings to showcase in her own solo show in Brooklyn. She’s also been working with white charcoal on black paper to bring out detail with white highlights. Her drawing style is also changing to be more vivid and colorful. She’s excited.

She was recently able to showcase her work with the RISE Movement, an organization seeking to Reach, Inspire, Support and Empower local New York artists. You can learn more about the movement on their Facebook or Instagram page.

“I don’t know if I’m the right person for advice…My hope for art is that it starts to include all stories. All experiences. It’s a job that all producers and consumers can work on. We can all create our experiences as Black artists but we also need that support from our communities. Black values are constantly talking about we need more representation, we need more Black art that demonstrates our existence, our experiences, our traumas. But the moment it comes to showing our support it gets kinda hard. And I get that, I completely do. I think there are ways to support that don’t require us to feel as though we are going beyond our means. I think that it’s as simple as being able to respect Black artists as more than just a fad and cry for a space dedicated to us. I guess that’s my hope.”

CHECK OUT MORE WORKS BY EUNICE:

Eunice Adounkpe showcasing sculptures and paintings with the RISE movement

Leave a Reply